One of the hot areas in AI research is image recognition. Accomplishment of this hasn’t been particularly easy and the problems include: recognizing types of objects such as a soccer ball or tree, identifying individual variants of an object such as distinguishing my black cat from a feral black cat that hangs around our house, and finding slight variations in objects that are similar such as a misshapen cell among normal cells that might be an indication of cancer. A common approach is to train neural networks by showing it images and adjusting how it works until we get the results we want.

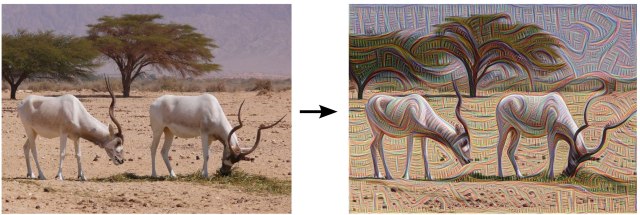

Many people are working on this and so it is not surprising to find Google to be among the companies most active. So what should we make of the bizarre and psychedelic images Google’s neural networks are producing when the neural networks are trained to emphasize features that would be used to recognition in existing images?

At first I must admit I was drawn to the images because of their resemblances to psychedelic experience. The transformation of the addax or white antelope reminded me of something from a LSD trip. The cloud transformations are like the faces and complex geometric structures I saw with peyote. Could my experiences have been nothing more than some internal visual processing software in my brain gone haywire?

Maybe so. But that does not mean we have to buy into all of the hype about these images. A fellow blogger, Donald J. Garcia, has written a more extended explanation and critique than I could and I won’t try to repeat his arguments that I agree with here.

Instead, I’d rather discuss blindsight. People with blindsight have damage to the part of the brain that generates visual consciousness. Many with this condition have it only on one side of the brain. When these people are presented visual stimuli on their blind side and forced to guess about the stimuli, their guesses are correct with a much higher accuracy than what would be achieved by chance alone. These people are processing visual information, and at some level even understanding the information, despite the fact they are not consciously seeing. In a sense, they are visual zombies.

Some estimate that as little as five percent of what goes on in the brain comes into consciousness in some form. Our brains processing visual information are doing exactly what the brain of those with blindsight are doing with the difference that the results make their way into consciousness. Under the covers our brains may be running algorithms like the AI neural nets yet the neural nets are as unconscious of the results as those with blindsight. Intelligence doesn’t require consciousness.

From where comes this peculiar light in our brain we call consciousness? Those with blindsight have damage in their visual cortex so we may be tempted to think consciousness arises there. The cerebral cortex is the massive layer of folded, gray matter that covers most of the brain. It is often associated with perception, consciousness, and awareness and its frontal lobes are associated with abstract thought and reasoning. Remarkably, however, damage to a small area the size of thumb in the brainstem can result in a deep coma. Mark Solms and Oliver Turnbull writes in The Brain and The Inner World: “We might say, then, that these tiny nuclei [in the brainstem] are the seat of consciousness. On this view, consciousness is generated not by specific cortical zones but by the activation of specific cortical zones by these deep structures (2002, p. 88).” These structures arose for the evolutionary purpose of monitoring and adjusting the internal states of the body. Consciousness is an extension of that function through engagement of the cerebral cortex.

It looks precisely like DMT when first breaking through. That is wild. I have read some on the blindsight thing too. At first it was thought it was replaced with the areas around it, but it seems to be more complex than a “clone stamp” effect. Definitely some algorithms doing patchwork in our heads!

LikeLike

Very much like the paintings of Pablo Amaringo.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I just googled him… and wow!!! Thanks for that reference!

LikeLike

Hi James

Thank you for linking to my post. That is very kind of you. Just a quick comment on:

“Could my experiences have been nothing more than some internal visual processing software in my brain gone haywire?”

For argument’s sake, let’s say that this is the case. What does it mean that you can actually >>see<< it? Isn't there something extraordinary about the fact that we could even be conscious of such a thing? To say it is "nothing more than" X is to underplay the fact that one is actually watching the inner workings of their own brain. Again, assuming we limit our interpretations to just this fact. Anyway, I don't want to dwell on it here but just conclude saying that the significance we assign to any interpretation of hallucinations is the key to that whole enterprise.

As to consciousness and the brain, I've written a few posts about that. You may wish to look them up. Specifically I cite Wilder Penfield, who was one of the greatest neuroscientists to ever work in the field. He was a philosophical dualist and I discuss why he came to this conclusion after spending his whole life studying and operating on human brains.

Again, thanks for reposting my article. I'll look forward to reading more of your posts and hopefully discussing these very interesting issues with you in the future.

Best wishes,

Don

LikeLike

Thanks, Don. And I have been following your blog and going back through some of your older postings.

LikeLiked by 1 person